On the morning of my scheduled Zoom conversation with Lauren Downing Peters whose book Fashion Before Plus-Size; Bodies, Bias and the Birth of an Industry, has just been released, an email arrives in my inbox on how internet searches for Margot Robbie’s diet exploded following the debut of Barbie. It seems appropriate as the topic of women’s weight will no doubt erupt again as another fashion month sweeps us up.

After last season’s runway shows, a New York Post headline screamed, “Bye-bye Booty: Heroin Chic is Back,” while the New York Times asked, “Why Did Ultrathin Models Make a Comeback at Fashion Week?” Amid reports that casting of mid and plus-size models fell by almost a quarter compared with the previous season, critics pointed to brands like Miu Miu and models like Bella Hadid for embodying the new skinny, while others argued that the skinny model never went away. Issues around women’s bodies often seems up for debate, but does the fashion industry and broader media treat the size of women’s bodies as just another trend like fluctuating hem lengths? FashionUnited unpacks the topic’s layers with Downing Peters before the dialogue heats up again.

On women’s size as a trend

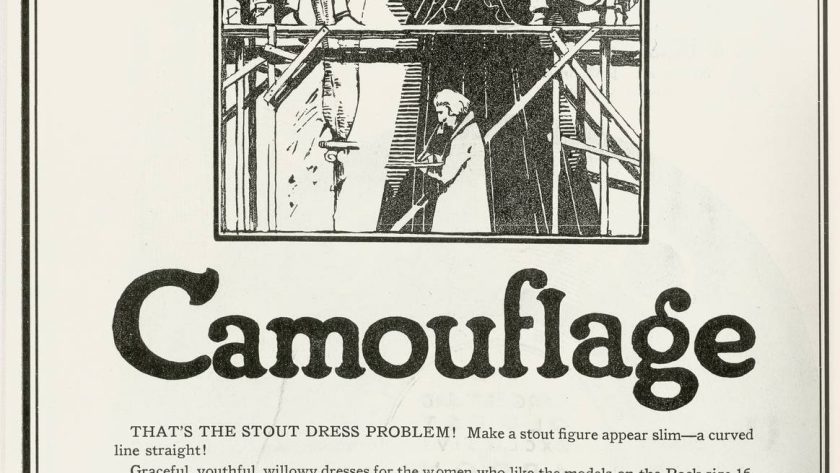

Throughout history there have always been periods when the fashion industry has been more or less inclusive of larger bodies and the cyclical nature of the headlines reflect the unfortunate reality that women are subjected to extremes diktats. The rounder figures of the 50s were replaced by the Twiggys of the 60s; the supermodels’ physical strength of the 80s was replaced by the vulnerable appearance of the 90s waifs. Downing Peters reveals that one of the more inclusive eras for larger women was the 1920s, despite its association with breast binding and the garçonne image of the Flapper. “American manufacturers produced clothing that had that tubular silhouette that was so popular at the time, but which was more inclusive of larger bodies,” she says. “We see that again in the 1980s, the next kind of moment where larger bodies were more permissible in fashion, which not coincidentally corresponded with that broad-shouldered, softly tailored silhouette proposed by designers like Giorgio Armani. Deconstructed suiting allowed for the fat woman in fashion versus that very clingy bias cut silhouette popular in the 1930s which really demanded a slender physique.”

On the accusation that body positivity movement promotes obesity

Women’s body size seems to be an issue that gets people riled up, almost like politics, with two ideals pitted against each other. The body positivity movement has been accused, often with immense vitriol, of promoting heart disease, diabetes, general ill-health, while the prevailing or default view seems to be that thinness equals healthy. “Framing it as a debate completely ignores the simple fact that the vast majority of women, especially in the United States and in parts of Europe, aren’t anywhere close to what would have been considered a norm or even an intermediate size in the fashion industry,” says Downing Peters. “67 percent of American women wear a size 14 or above, that’s the vast majority of American women.” This oversimplification frustrates Downing Peters who sees it as an ignorance of women’s realities and, from a more cynical point of view, reflects a narrow-minded business perspective.

“The first most obvious point to remember is that the fashion industry doesn’t care about our health,” she says. “The industry wants us to buy things. They’re the architects of fashion trends encouraging us to buy more and to make us feel insecure and to want to use fashion to change ourselves and our appearance.” An indicator of the industry’s lack of investment in our personal health is the insidious persistence of the Heroic Chic aesthetic which has been around for thirty years. Says Downing Peters, “It’s had an incredible kind of longevity because it does stand as this pinnacle of subservience to the fashionable ideal. But the very name of it is meant to recall a person wasting away.”

On terminology

“I’m interested in exploring these larger systems and practices that established norms and help us to understand what constitutes a fat body in any given era,” says Downing Peters. “And it’s worth noting that whenever I use the term I’m not doing so pejoratively. I’m using it in the kind of scholarly and activist sense of the word, or as a neutral descriptor.”

Like other reclaimed descriptors, the word “fat” provokes much handwringing. It’s perhaps more freely used among Gen Z but many larger-bodied women of older generations won’t use it because of how it has been used to inflict trauma on them in the past. Others who take their cues from them find the word shrouded in uncertainty and confusion. Downing Peters, who is also a university educator describes how her school is introducing a plus-size design minor, but broaching discussions on draping for the larger figure and issues of size inclusivity provokes significant discomfort among faculty.

So is the term “Plus-Size” useful or should we be using something that’s more reflective of 67 percent of society? Is othering the way to include? “People do perceive the term as being pejorative because it does very concretely create a threshold between standard sizes, which are normal, and plus sizes, which are deviant,” acknowledges Downing Peters. Calls to abolish the term over the years have led to alternatives such as the use of “curve fashion” which is more palatable to some. But, says Downing Peters, “Until the fashion industry is truly inclusive to the extent that any woman can go into a store and buy a garment from a size 00 all the way up to a size 40, plus-size is a really useful term for navigating a biased marketplace.”

On the idea that people weren’t plus-size in the past

On the prospect of reaching true size parity, Downing Peters doesn’t mince her words. “I think it’s a huge challenge. It would really take a wholesale reimagining of how fashion is produced.” In her book, Fashion Before Plus-Size, she explores how standardized sizes emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when manufacturers were looking to scale up production, basing their systems on an ideal body type that has stuck around all these years later. According to trade journals going as far back as 1915, upwards of 30 percent of women couldn’t wear the new standardized mass manufactured clothes of that time, so the idea that in the past people weren’t plus-size is a myth.

We’ve been led to believe that fashion relies on the “trickle down effect,” the phenomenon that what happens on the runway directly informs what people will be wearing on the streets. But Downing Peters’ research indicates that the mass market standardization that debuted during the Industrial Age is so ingrained in our system that no runway imagery or high profile body positivity moment can unseat it.

On the longevity of the Body Positivity Movement

We’ve seen society embrace the fuller figures of Lizzo, Selena Gomez, Lena Dunham, but questions now arise around the longevity of the body positivity movement and how transformative it has actually been. “The rise of plus-size models in magazines and on runways coincided with the explosion of athleisure and the turn towards comfort in fashion,” says Downing Peters. “For a brief moment that enabled us to see maybe not a wholesale reimagining of what beauty can be but perhaps a slightly enlarged version of it, and this allowed the average consumer to see that beauty is a construct, or that they can be comfortable and creative and innovative in their own self-fashioning practices.”

But the fashionable silhouette du jour tracks with what society views as the ideal body. Since the emergence of the body positivity movement there has been a new sea change: the Y2K aesthetic. “The return of low rise jeans, crop tops, these kinds of clothes, demand a slender physique for the look to work holistically,” says Downing Peters. “We have moved away from comfort and body acceptance, or at least body neutrality, into an era in which the rise of Ozempic as a weight loss drug vies for headlines with the rise of Heroic Chic as a fashion look.”

On the absence of a plus-size men’s movement

It’s difficult to think of a brand which represents plus-size men’s fashion or indeed a model that represents the category in the same way as Ashley Graham or Paloma Elsesser or Tess Holliday. Are women somehow ahead in this field in terms of representation or is it that men are less subject to body categorization?

“Plus-size men’s fashion isn’t a thing because menswear and specifically men’s tailoring has always accommodated bodies of different shapes and sizes,” says Downing Peters. British and American tailoring journals from the 18th century through to the early 20th century feature tailors boasting about their ability to create innovative tailoring and drafting systems to accommodate even the largest men, offering suits in 200 different sizes that take into account different disproportions. “This bodily diversity was not seen as a problem but as an opportunity to show off the craftspeople’s artistry,” says Downing Peters. Categories between the standard male body and the fat body were therefore not created.

“Tailors, especially those who were working at the highest level of the craft, saw all bodies as having what they referred to as disproportions that the power of their tailoring could correct, whether that be a stooped shoulder, hip imbalance, stomach protrusion, they were all viewed the same.” In early twentieth century advertisements, off-the-peg retailers even challenged consumers to come in and experience the perfect fit. Downing Peters argues that this thinking persists in menswear today. “Men have had more leniency with being larger in our society, and size can oftentimes be a symbol of power, or pride, even aligning with athleticism when you think of an NFL linebacker,” she says. “As with everything, women are subjected to stricter moral guidelines on what constitutes an acceptable body.”

On fashion as art

Some might argue that fashion is an art form, part of a visual culture that should not be subjected to such mundane requirements as being reflective of society at large. A form of escapism, fashion, like Hollywood, is about selling dreams and if romantic comedies don’t reflect our real lives, why must runways do so? Even putting aside the commercial enterprise that is fashion, Downing Peters finds this argument flawed. “Good art is always political, and some of the greatest artistic movements actually anticipated larger societal shifts and changes, where artists were using their medium to imagine a different future,” she says. There is little argument that fashion can be art, especially when considering the level of craft on display during couture fashion week. “But good fashion, is actually a mirror of our times,” says Downing Peters. “It can affect the way we see and perceive things, and this applies to beauty and body ideals as well.”

If anything it is a lack of artistry around plus-size that is the problem, a lazy design approach that can also be traced back to the Industrial Age. “Manufacturers were calling larger women freaks, talking about their mental instability, about how they were sad and how they didn’t have to work so hard to design beautiful clothes for them because they were needy and would accept whatever they gave them,” says Downing Peters. This continued lack of aesthetic commitment to plus-size innovation makes the larger customer’s shopping experience inherently unsatisfying. “The bar just isn’t as high for a large size dress because it’s impermissible to be contentedly fat in Western society,” says Downing Peters. “We live in a diet culture where we’re always in pursuit of something else, and a fat body is always a body that is liminal and in transition, and bias, both conscious and unconscious, in the fashion industry enables these narrow mindsets to persist.”