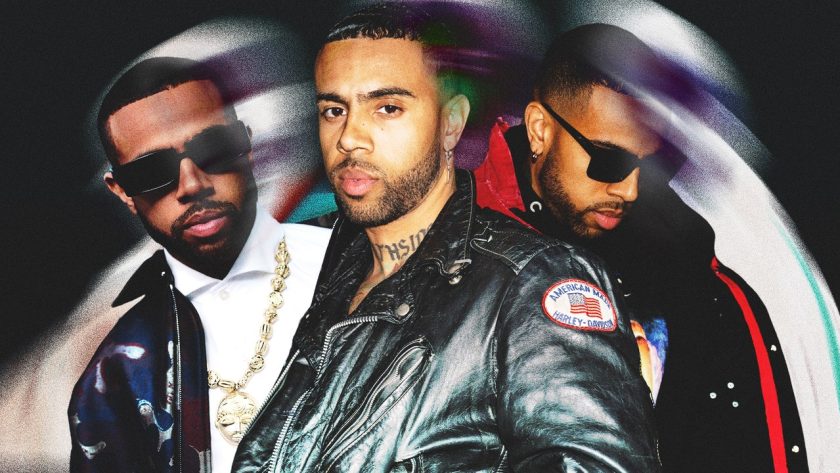

“I’m not a villain,” says Vic Mensa. It’s a Tuesday afternoon in late September, and the Chicago rapper is calling from L.A., where he’s preparing to join his longtime pal Chance the Rapper at the latter’s Acid Rap 10th anniversary show at Kia Forum. There, Mensa will perform his breakout mixtape INNANETAPE – which also turns 10 this year– in its entirety. The anniversary has him feeling reflective on his career thus far. “I was oftentimes very despised in the music industry,” he admits. “And sure, you got some people that are like, ‘I’m a demon, I’m a savage, I’ll stand on it!’ And I respect that. But that’s not me.”

Vic is ready to make amends. It’s been a weird and not-always smooth past decade for him. He broke onto the scene alongside Chance circa 2013, linked up with Scooter Braun, signed with Roc Nation, released a debut album, championed the downtrodden by sleeping outside with Chicago’s unhoused and joining Sioux Nation water protectors at Standing Rock, dissed the likes of Drake, Lil Yachty and XXXtentacion on wax, was arrested on separate gun and drug charges, got sober, and this past spring, owned up to his mistakes and tribulations in a no-holds-barred freestyle on Sway In The Morning. (Regarding that show-stopping verse, Vic tells GQ he’s “been working on something to go rap on LA Leakers in the vein of the Sway freestyle.”)

Victor, his second full-length LP, finds Mensa staring down his anxieties (“Blue Eyes”), navigating his push-pull with religion (“Sunday Evening Reprise”) and coming to terms with his complex relationship with his native city (“$outhside Story”). Throughout, Vic is a repentant and well-versed and always straightforward narrator. “I’m shedding light on shit that people might have only seen one side of,” he tells GQ. “I’m looking to constantly keep growing. I don’t want to be entrapped by the same thought processes that maybe held me hostage in the past.”

GQ: Victor is a bloodletting. You’re freeing yourself of a lot of negativity that’s surrounded you in recent years.

Vic Mensa: For me, to emerge from so much pain and trouble and controversy and darkness, it could only really work in tandem with music. It’s also a labor of love in the truest sense. Because the shit ain’t easy. Neither the creation of the music or the life experience that was required of me to make this music, none of that is smooth sailing. It’s just hard work. Discipline. Focus. Patience. Faith.

When did you realize this album was going to be you coming to terms with the past decade of your life?

Oftentimes I’ll do some things that are outside of that world—maybe a freestyle that’s all about punch lines or a single that’s something more fun—but I associate the making of an album with a real personal upheaval. I was talking to Mick Jenkins yesterday and he likened it to excavation. It’s like mining inside of myself to strike gold. But that doesn’t mean you don’t have to chip away at a million rocks before you find that piece of gold. I have a litmus test almost for what I think is going to be the dopest and hit the hardest. When something gives me shivers, chills while I’m writing it or even brings me to tears—some lines will—then usually that’s when I know I’ve struck upon something.

You’re clearing your conscience on Victor. It feels like a continuation of the freestyle you performed on Sway this past spring in which you essentially apologized for dissing everyone from Drake to XXXTentacion and Lil Yachty.

One hundred percent. That freestyle was a part of the album process, for sure—the same things I’m talking about in the freestyle, I’m talking about in the album. I’m illuminating the multi-dimensional depths and experience that someone might have just flattened into a headline and not had the context of understanding. On the topic of misunderstanding, I’ve always felt misunderstood. I mean, even culturally. Growing up on the South Side of Chicago but being African but also being white in a black community… that’s a perfect storm of misunderstanding. So that’s always existed in a sense.

But even more recently, in a professional sense, I definitely do think that I started to feel very misunderstood and to be seen as a villain. And (I feel) very beloved too by a lot of people—but I think as human beings we’re predisposed to put more weight on hate than love. It was something I wanted to break down. I know I’m not a villain. The things I’ve done in my life are not perfect by any means. But anybody that actually knows me with any type of comprehension knows that I’m the opposite of a villain. My impact on the world has by and large been very positive compared to the negativity that I have indulged in. I’m on a short list of rap artists that have done as much to serve and empower the people as I have. From giving away millions of dollar’s worth of shoes in (Chicago’s) Englewood (neighborhood) to supporting the Native American community at Standing Rock and Palestine and training first responders in the ghettos of Chicago. I’m not a villain. To be seen as one though because of some industry things and mistakes I’ve made, ways I’ve phrased things, was a conflicting experience.

Well, you know what Katt Williams says: if you ain’t got no haters, you’re not doing something right. And if you’ve got five haters this summer you need 10 by December. But at the same time, I think even more than a public perception of me—the things I’m discussing in this album are, how do I act with integrity? How do I recognize what my role has been in all of this? And just realizing that some of the ways that I’ve moved through the world are contradictory and conflicting. That’s oftentimes the case of the Gemini. You can’t really have it both ways: if you want to plant your flag and stand on being a champion of freedom and justice and the things you’ve dedicated your real life to in this last 10 years, then it doesn’t also work for you to run around and be the motherfucker that’s nudging left and right and beg in controversy. Because it casts a shadow of doubt on the validity of how much you mean what you say when you’re standing up on these high ideals.

Coming to understand that, that’s been super powerful for me. Because it helps me to purify my purpose and my direction. That doesn’t mean to be a perfect person and create some facade of moral high ground. It actually means to tear that shit down. It means to be vulnerable, be honest, be human but to be of integrity. To be integrated. Not one day you’re all about positivity and the next day it’s like your gun charge is on TMZ. Figure it out! Which one do you want to be? Do you want to be freedom and March For Our Lives. Or do you want to be in fucking jail with a gun? Which one?

It’s funny because originally Save Money was looked at as the woke side of rap? Though, “woke’ has become a co-opted term in itself.

Nah, but they can’t take woke from us. That’s the thing though. The people that have spearheaded this anti-woke movement, they didn’t create woke. Woke is born of civil rights, black artists and activists. Nah. Stay woke.

You’re of mixed race, and on “Blue Eyes” you’re rapping about the self-doubt that caused in your younger years: “I would stare at my parents and wonder why my appearance was different, used to wish I was white, would fantasize.” Tell me more about this song and its genesis.

Man, I started writing that song in 2016. I did ayahuasca for the first time and I was hella depressed. And I was asking “Why do I feel so much pain?” I had this higher voice come to me and say, “I used to want blue eyes. That is the root of pain.” So I started writing that song. But I didn’t have the rest of the words. And then more recently, my aunt in Ghana got skin cancer and then I learned that she had a history of skin bleaching. I was really floored by that. Suddenly I felt like I had the words for the song. That was the only thing I could imagine to do with that heavy of an emotion. It was a song I’d been trying to finish since the idea way back in 2016. Obviously it very explicitly speaks to the condition of African people in a white supremacist society. But I think at the same time, and perhaps even in a broader sense, it’s a message of self-acceptance and self-love to anyone.