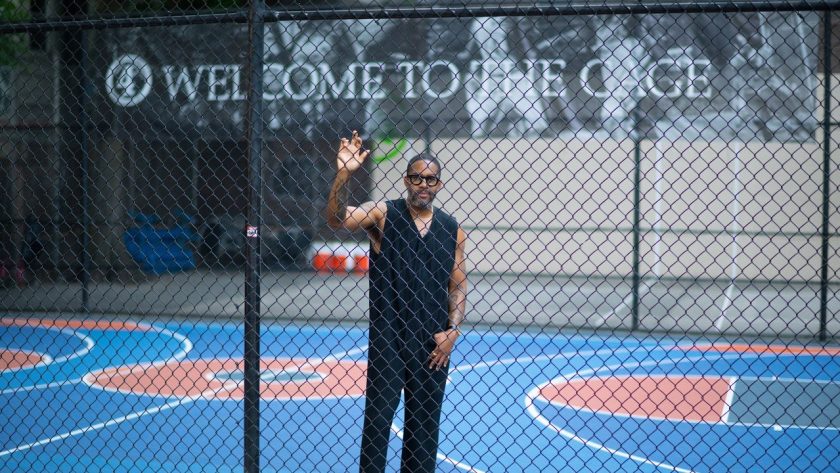

“On the page, I’m always thinking about patterns and textures,” Jackson explains. The pop of vintage diction, the deployment of bespoke Black slang, are hallmarks of a Mitchell Jackson paragraph. Such attention to detail extends beyond the page. Having just arrived in New York from Phoenix, where he teaches writing at Arizona State, he found that his hotel room wasn’t ready, so he was unable to change into his planned outfit for our meeting. Nevertheless, his travel uniform still demands mention: black Yohji Yamamoto flight suit—he always brings two, so he can wear a fresh one back—and Yeezy foam runners. He resembles a suborbital space pilot from the future, hair low and waved up, salt and pepper beard, calm but watchful eyes behind oversized black-framed glasses.

Later that evening, an email with a selfie hit my inbox. For the record, Jackson, ever the perfectionist, offered a clarification: “Had I worn what I intended to wear, it would’ve been this white Thom Browne shirt, Comme des Garçons slacks, and Thom Browne brogues.” What follows is an edited and condensed version of my conversation with the author about the evolution of NBA style, generational attitudes towards masculinity, and why writers are so drawn to basketball.

Mik Awake: What was the most interesting thing you learned researching Fly?

Mitchell Jackson: One interesting thing for me, research-wise, was the 1980s. It’s called the Jordan era in the book, but Jordan didn’t hit (the NBA) until 1984. So I actually started that decade with Reagan, right. Because Reaganomics was what changed the eighties. And I started thinking about all the shows I was watching like Dynasty and Knight Rider and Magnum PI. All those shows are shaped around affluence—and Miami Vice with the drug war. So for me, yes, it’s named after Jordan, but we don’t get to the boom of television and the resources that ad companies had to pay. Those eighties are so much shaped by economics. And even if Jordan was as good as he was, if the NBA didn’t have TV, if TV wasn’t what it was, which meant advertising was what it was, Jordan could not have become a global icon. Nike took a huge risk economically on him. But if we don’t have the Reaganomics in the eighties, Nike ain’t even booming like that.

Do you have a favorite photograph?

One of my favorite photos was of Pistol Pete. When I was young, Pistol Pete was basically Kyrie Irving. He had The Pistol Pete Maravich Tape to learn how to dribble. I didn’t have the tape, but I saw it somewhere. Maybe one of my homeboys had it or something. And I mean, he was flamboyant. And so when I saw the picture of Pistol Pete wearing a butterfly collar, a diamond chain with his name on it, and those big seventies sunglasses too…That was like, “Oh, that’s exactly who I thought Pistol Pete is.” His clothing was a representation of the way that he played basketball.

A considerable portion of the book seems to be tracking an evolving idea of Black masculinity. How do you think NBA fashion fits into that?

I think a lot about masculinity. I’m really always writing about that in some way. I think the changes are really owed now to LGBTQ+ and gender-nonconforming people. They gave Black men, some Black men, younger Black men especially, the freedom to express different sides of themselves, to be vulnerable in ways that they weren’t previously or they didn’t feel like they were allowed to be. And I think it’s an evolution because, well, we think if we go back to Antebellum South, they were emasculating Black men. They were literally cutting they things off. So that what we think of maybe as hyper-masculinity, or some people call toxic masculinity, is a reflex response to emasculation. It’s in many cases gone overboard. So I’m happy to see people like (Russell) Westbrook and Shai (Gilgeous-Alexander)—I mean, half the young dudes now painting their nails. I feel like they feel a sense of freedom that even ’Bron and them didn’t feel. Dudes like Kelly Oubre, Jr., or Shai, or Jordan Clarkson, Jalen Green—all those dudes are really pushing what is masculinity. I think that’s maybe what it is. They’re redefining it for themselves, which every generation does: define themself against the other one in some way.

How has social media impacted fashion in the NBA?

Back in the mid-’90s, the custom-suit dude used to come to the players’ room, measure ’em all up, show ’em all the fabric, and then that’s what you wore to the games. But these dudes who come in now, because of Instagram and social media, they’re so much more advanced in their sense of fashion and what’s available to them. They’re already seeing fashion shows online. They’re already watching dudes in the tunnel. They already have a real facility with brands that the N.B.A. players of yore did not—could not have had. They wouldn’t know who the new brand is. So I think now there’s also much more competition, and I’m not the first to say this, but the idea that you could be famous without actually playing basketball. Now all you got to do is make it to the league and get a contract big enough for you to buy some clothes. And you can actually be famous. There are some dudes in this league who are more famous for what they wear than their game. So I think all of those things are really different. And certainly the custom suit guy is out. Ain’t nobody getting customs. If they getting a custom suit, it’s from Dior now.

Why do you think basketball is such rich territory for African American literature?

(The author John Edgar) Wideman and I did an event—I don’t even know what book it was for—but we were talking about basketball and what we were talking about was how basketball is jazz. You practice, you practice, you practice so that you can actually improvise. And I think there’s something to the Black experience that demands improvisation. There’s also something to the Black experience that improvisation becomes really beautiful and it becomes something that other people admire. You do more with less and it actually becomes cool…