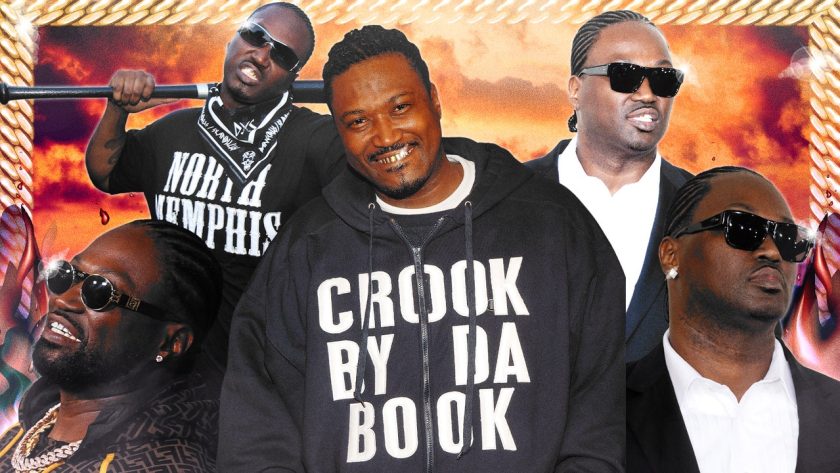

Offset’s weekend was a momentous one. The Atlanta rapper’s recent ubiquity is to further the promotion of his new single, “Fan,” from his upcoming album, Set It Off . The video’s incredibly endearing reworking of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” got all the headlines, but amidst the salute to the King of Pop, there was a sonic homage just as culturally important. Toward the song’s end Offset lifts up rapper Project Pat, whose style of rhyming—especially over the past decade, along with the production style of his Three 6 Mafia family—has been the foundational element of a solid batch of hits from rising stars within hip-hop. Set’s nod to the Memphis legend reenergized online conversations about Pat’s influence across rap over the years, highlighting that fans of his find it crucial to sing his praises in a time in which popular artists from the past are at risk of being phased out of collective consciousness.

Project Pat is a rap maestro that often gets his just due from passionate listeners of Southern hip-hop, but rarely from institutions and figures that shape what casuals view as extraordinary work. As criminal as it feels, he’s hardly the only occupant of grazed over space—especially under the Mason-Dixon line. Northern rap elitism also tells us (or at least implies) that Pimp C isn’t one of the greatest to ever touch a mic or drum machine, that Webbie didn’t have one of the genre’s strongest debut albums in history or that La Chat shouldn’t get any airtime when considering the best women to do this thing. But let’s be honest here: the twang and bounce that came from these artists has been a tremendous help in kicking hip-hop into the abundant stylistic reality that we enjoy today. And regardless of the resistance it’s faced over the years, the truth is in the music.

Pat raps with a deceptive simplicity, an elastic style that’s instantly addictive and catchy. Take “North Memphis,” the first song from his first album, Ghetty Green. In rapping, “Breaking down some reefer, rolling up a sweet-ah/ Riding through the street-ah, chiefing like a heat-ah,” to open the track, he set the stage for his ability to make language bend to his authority. He accentuated words in a way that used to make listeners hang onto every line—establishing a shared lingo for us to look forward to engaging with. Fixing vehicle (“ve-hi-colll”) to align with liquor (“li-koohh”) or adding extra syllables to shit (“shizz-irt”) so it can rhyme with “outskirts” (“If You Ain’t From My Hood”) requires some real imaginative thinking. In early interviews, he attributed the style to copying nursery rhymes as a template for flow when he was first starting out. Even in The Source shamefully assigning Ghetty Green 2.5 out of 5 mics in 1999, they had to concede: “he should be given more credit for developing a style that will easily stand out in today’s crowded world of MCs.”

But deeper than style is Pat’s gift for storytelling. “We Can Get Gangsta” is a seat-grabber, similar to what rap fans in recent memory liked about King Von’s “Crazy Story” series. On it, the North Memphis native recounts a situation in which his homeboy Gangsta Fred gets an inquiry to serve some guys from across town that they don’t know too well. Pat is apprehensive, but agrees. And for four minutes, he takes us on a play-by-play of meeting up with the prospective customers, sensing that they’re shady characters and getting into a gun fight which leaves Fred shot and the others dead. On 2002’s “Choose U”—over the same Willie Hutch-sampling beat that DJ Paul and Juicy J gave to Outkast and UGK for their widely revered collab “Int’l Players Anthem” five years later—he taunts a man about taking his woman, detailing how she likes to ride in his truck and how he’ll “get a extra couple of G’s” claiming the dude’s kids during tax season. On “Try Somethin” from Three 6 Mafia’s Da Unbreakables, Pat bounces through lines telling us how he robbed someone outside of a strip club while they were in the middle of peeing. This is the ingenuity of someone who’s so comfortable in their style that it raises the antennas of others, prompting them to come, learn and borrow for their own usage.

Long before Offset tipped his hat to Pat in “Fan,” artists have been leaning on his style to establish hits and to win crowds over. And it works. That’s why Cardi B drew from Pat and La Chat’s “Chicken Head” for her 2018 single “Bickenhead.” Skepta had no American listenership to speak of before incorporating a Pat-like rhyme scheme to his 2014 track “It Ain’t Safe.” Blocboy JB was relatively unknown before he and Drake teamed up for his career-launching “Look Alive”—Drake’s impressive verse interpolates Pat’s “Out There (Blunt to My Lips).” Pat’s cameo in Drake’s “Worst Behavior” video (shot in Memphis) was an OG stamp of approval and Drake took it a step further a couple of years later, fully pasting a Pat verse in to set the scene for his 21 Savage collaboration “Knife Talk;” Savage’s Pat-influenced contribution steals the show, elongated ahhhhs at the end of his bars and all. Even the genre-shifting Gucci Mane spent the earlier portion of his autobiography outlining how no other rapper quite captured his life as a young hustler and jackboy like Pat did, giving him inspiration on how his own music needed to feel.

Right now, Project Pat doesn’t appear incredibly occupied with music, outside of acknowledging his music being sampled by rap standouts and showing up as an unexpected guest on Blood Orange’s Negro Swan album in 2018. The most recent stage of his life has been in service to the incarcerated, by way of preaching. In an interview earlier this year he detailed searching for newfound purpose and landing on a vision to engage with folks living under circumstances that he’d experienced firsthand. And so, in the truest sense, Project Pat is extending his legacy as a messenger. Someone striving to strike a chord within others by sharing his own stories. He is a generational artist, one whose impact laps many that are routinely lionized before him. I’d like to say I dream of a world in which Pat was given the same credit, but there’s more power in the fact that artists who were small children — if born at all — during his run recognize his magic so much that engaging with it offers them the chance to pull people in with that same level of face-scrunching pleasure.