With its state-of-the-art glass and copper-colored steel facade, Thélios‘ Longarone manifattura, or factory, in Italy’s Veneto region borrows materials from the eyewear produced inside. But while the vibe is industrial, the building bears more of a resemblance to a contemporary art gallery than a manufacturing facility. (The picturesque backdrop of the Dolomite mountains only adds to that effect.)

LVMH created Thélios in 2017 to take control of its maisons’ eyewear, previously produced under license. It inaugurated the Longarone facility a year later with the goal of taking everything — design, production, distribution, the whole shebang — in-house. The 215,278-square-foot space crafts sunglasses for LVMH Group brands, including Dior, Loewe, Celine, Fendi, Fred and, as of next year, Bulgari. It has a yearly capacity of around 4.5 million eyewear frames, and employs 1,000 people. If you’ve been following Beyoncé’s Renaissance Tour wardrobe, this is the place responsible for Givenchy’s sci-fi inflected Giv Cut glasses, which the artist has been sporting in various permutations throughout — not least those 3D-printed versions, custom-set with crystals.

Photo: Stefanie Rex/Courtesy of Thélios

As with beauty, sunglasses serve as an important first access product for luxury customers. As CEO Alessandro Zanardo tells Fashionista, the objective with Thélios was to elevate this category, ensuring that it reflects and represents LVMH luxury brands in terms of both quality and creativity. “If you want to have an excellent product, in a reliable time, in keeping with the rest of each collection, you need to have direct control,” he says.

Thélios wanted the manifattura to be “the place where the best know-how for the category was concentrated — the best designers, prototypers, technical persons we can find,” Zanardo adds. “The final outcome must have no compromises.”

To ensure total alignment in terms of creative and brand identity, he continues, “there has to be a real partnership and constant dialogue with each respective house, working together to translate the design briefing into something that can be produced industrially.”

Photo: Stefanie Rex/Courtesy of Thélios

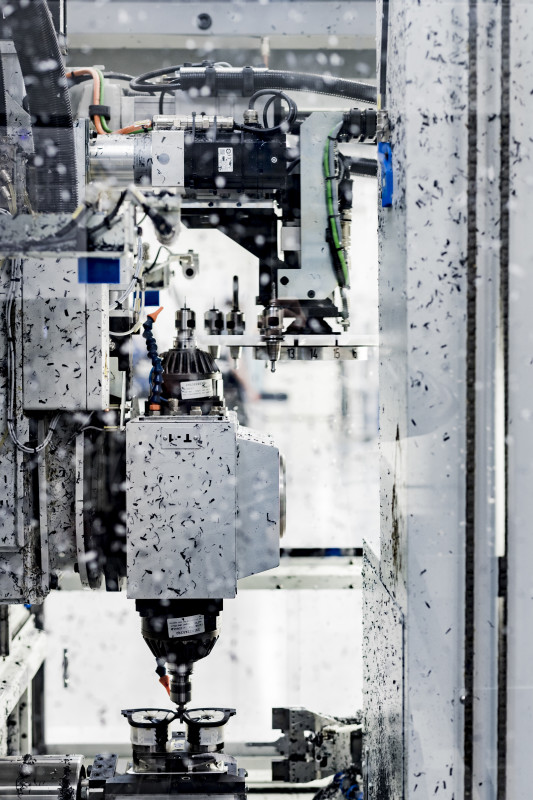

An example of this might be Loewe’s bulbous Inflated eyewear styles, the concept of which was drawn from the surrealist balloon footwear of Jonathan Anderson’s Spring 2023 collection. The journey starts in the manifattura’s prototyping department, where designs are first rendered digitally using CAD software. The raw files “can also be used to create the digital assets that support the launch of the physical products,” says Prototyping Plant Manager Enrico Cori, demonstrating on a giant touchscreen.

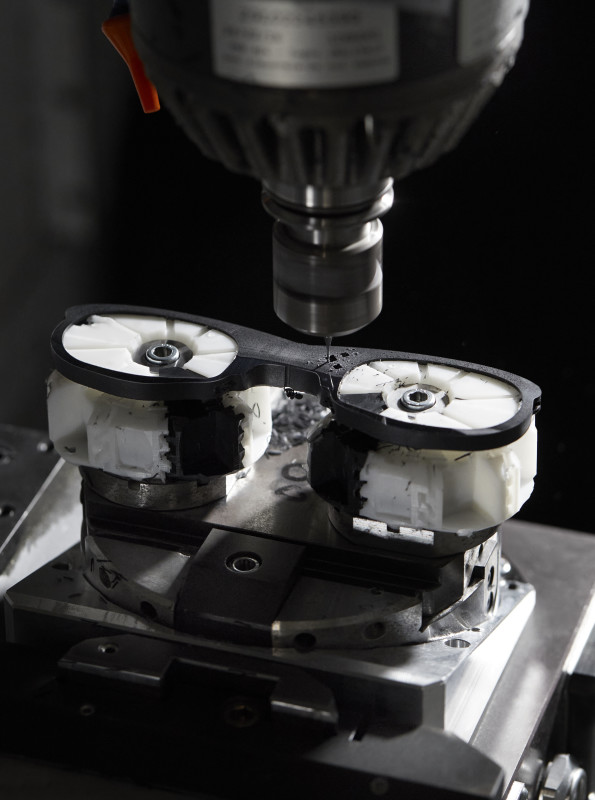

Next step is creating physical prototypes from the digital files. Each part of the frame is made using a different machine that specializes in a different process and uses a different program: One cuts the rims to shape, another cuts the arms (the technical term is “temples,” by the way), another inserts wire into the acetate so that it holds its shape (which involves heating the temples to 200 degrees and then fixing them by suddenly reducing the temperature). This takes between eight to 20 hours to complete.

Photo: Giovanni Samarini/Courtesy of Thélios

Once the prototype has been finished, 20 pieces for each model in each color are created in the industrialization area, to ensure that they can be successfully produced at scale with no hiccups. Then comes production, done using industrialized versions of the prototyping machines, which are lined up in phalanxes across vast factory floors; some are programmed to operate 24/7.

Each frame involves more than 80 different processes. There’s a machine for polishing the frames from the raw acetate to a brilliant gloss, which involves tumbling them with a range of different sizes of wood chips. “It’s like a tumble dryer,” says Cori. “It rotates the chips, and the pieces of wood hit the acetate to make the surface shiny. You need to set different timings for each phase of each frame.”

Photo: Giovanni Samarini/Courtesy of Thélios

Some steps are executed by skilled craftspeople and artisans that undergo two years of training at Thélios. For instance, tiny metal logos on some of the Celine and Dior frames must be painstakingly applied by hand so they fit flush into the equally tiny debossed letters laser-cut into the temple itself. “They need to be dropped parallel to the frame at the correct angle,” Cori explains. “You have to be really careful to avoid any bubbles or dust.”

Lenses are the only element of the eyewear not produced in-house. However, they’re fitted and finished at the manifattura. (The logo on the lenses of those oversized Fendi Baguette frames, for example, are done by masking parts of the surface with a stencil, and then spraying them with vaporized metal oxide.)

Photo: Giovanni Samarin/Courtesy of Thélios

The aforementioned 3D-printed Givenchy Giv Cut glasses (and also Fendi’s recent Shadow model) are produced inside a giant cabin in the prototyping area that looks like a cross between a tanning booth and a mountain cable car. Inside sits a machine that heats the powdered nylon base component in precisely programmed layers, so it changes to a solid in the necessary areas. The result is a packed block of powder — “once the excess is shaken away, you find the finished pieces inside like a fossil,” Cori says.

According to Zanardo, the 3D printing techniques introduced by Thélios last year had previously been used in the eyewear industry, but not in luxury eyewear. “That was the innovation, being able to elevate the quality so it could be considered comparable to other techniques and materials used for luxury eyewear,” he says. While he admits that the volumes produced are not vastly significant, he’s adamant that “it makes a huge strategic impact” on the business: “The time to market is usually quite long in most luxury categories, but with 3D printing, it’s practically ‘see now buy now’. That’s the big thing.” (Cori adds that 3D printing is especially useful for unusual geometrics, because you’re not constrained by a mold.)

Photo: Ava du Parc/Courtesy of Thélios

Photo: Giovanni Samarini/Courtesy of Thélios

Sustainability is not only addressed by the 2,529 solar panels on the manifattura‘s roof, but also in its development projects: The company is working on a new version of acetate that substitutes some of the chemicals for biological materials, for one.

“In the past, sustainable materials were less qualitative, meaning they were of a lower standard in terms of performance,” Thélios Product Development and R&D Director Carlo Roni says. “We’re mixing together different kinds of materials to reach a solution.”

Earlier this month, Thélios announced the strategic acquisition of French heritage outdoor sunglass brand Vuarnet, which was co-founded by optician Roger Pouilloux and French ski Olympic gold medallist Jean Vuarnet and remains one of the few eyewear labels in the western world to produce its own mineral lenses. While glass is, by definition, a more sustainable option than plastic, Vuarnet’s output is also known for its performance capabilities, in that it combines unparalleled strength and lightness.

“It’s not a matter of Thélios’ adding more and more brands,” Zanardo argues. “There are some in the market that have a very high quality in heritage, iconic design, know-how or customer perception that make them really unique.” Vuarnet’s mineral lens capability was a major draw: “We’re happy to integrate in our industrial set-up and develop it.”

Disclosure: Thélios paid for the writer’s travel and accommodations to report this story.

Want the latest fashion industry news first? Sign up for our daily newsletter.