“When looking at clothing and memory, I wanted to think about the experiences we all share. We were all born. We were all children. If we are lucky, we will grow up and then old,” says curator Elisa De Wyngaert of her latest project, the multimedia exhibition ECHO. Wrapped in Memory. “It is not about bombastic, monumental stories, but ordinary and intimate ones.” Opening on October 14 at MoMu, the Fashion Museum of Antwerp, the show explores these simple facts of life via the lens of three creatives: the visual artist Louise Bourgeois, the choreographer Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, and the fashion designer Simone Rocha.

ECHO explores something profoundly universal: the meaning we attach to what we wear. Who hasn’t struggled to part with the dress they wore to their first dance, even if it stopped fitting decades ago? Or the first designer item they ever bought, even if it’s worn to the ground? Bourgeois was extraordinarily sentimental about her clothing: “It gives me great pleasure to hold on to my clothes, my dresses, my stockings, I have never thrown away a pair of shoes of mine in 20 years,” the artist wrote in 1968. “I cannot separate myself from my clothes nor from (her son) Alain’s — The pretext is that they are still good — it’s my past, and as rotten as it was, I would like to take it and hold it tight in my arms.”

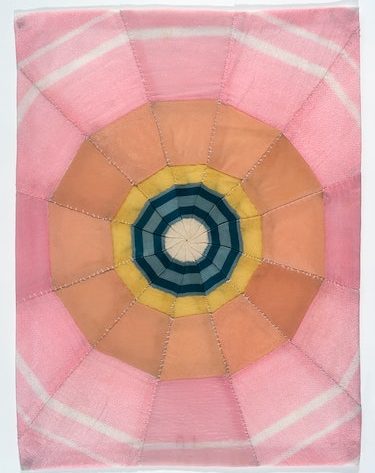

Louise Bourgeois – Dawn (detail), 2006. Photo: Christopher Burke, © The Easton Foundation/SABAM Belgium 2023

Gown made by C. Palm, The Hague, c.1900-1905, MoMu Collection inv. T12/1309/J236 © MoMu, Photo: Frederik Vercruysse

Rocha similarly hangs onto pieces. “With my own designs, we have an archive, and we keep one of everything,” she explains. “But then I also have quite a rich vintage archive mix of my own clothes and source clothes that I really treasure. I have some garments from when I was a little girl that my daughters now wear. My youngest daughter was in a blouse the other day that was one of mine, and it was just amazing to see it on her.”

It may seem unusual for a fashion exhibit to feature a dancer and choreographer, but De Keersmaeker’s work is a natural fit. Her first solo in 1982 was inspired by the movement of her dress. “Clothing is very important to me as a choreographer,” she says. “The structure, the materials used, the color, the transparency of a garment, how it responds to or magnifies a movement—so many different facets of clothing play a role in the choice of costumes. Clothing is an extension of the body.”

Rain, 2001, Cynthia Loemij, Rosalba Torres, Alix Eynaudi, Fumiyo Ikeda © Foto: Herman Sorgeloos

Motherhood, memory, and its cousin, nostalgia, are themes woven thickly throughout the show. A childhood drawing by Martin Margiela of his grandmother hangs alongside footage of de Keersmaeker’s early works. Also featured in the exhibition are photographs from Harley Weir’s Function series, which explore the biological and societal functions of the female body; an installation by Marianne Berenhaut, Le Pouf, which features a delicate pointelle christening dress laying atop a satin pouf; and a silk painting by Billie Zangewa that portrays a typical moment of domesticity, titled Mother and Child. Also in the mix, alongside historical garments and pieces from MoMu’s impressive collection, is work by the artists Cassi Namoda, Cathy Wilkes, Maya Bareera, Laila Gohar, and Liz Magor, as well as the designers Raf Simons, Helmut Lang, Dries Van Noten, Meryll Rogge, and Jurgi Persoons.

Louise Bourgeois – Blue Days, 1996. Private collection, New York. Photo: Christopher Burke, © The Easton Foundation/SABAM Belgium 2023

“There are pregnancy corsets, and all these beautiful, almost childlike handmade shoes—these pieces that have had this purpose around mothering or loving or protection or birth,” says Rocha of the archival artifacts featured. “It was really surprising how they can speak the same language as the sculptures of Louise or the movement of Anne, and then how my clothing can also come into that dialogue.”

ECHO closes with an installation by Bourgeois titled Blue Days, which has never been shown in Europe before. The piece features various items of clothing hanging from metal poles, “In these, she conjured her past selves, her childhood and family members, invoking them by the clothes she had once worn, ensuring that her memories would not be lost,” explains De Wyngaert. “While arranging the loan of Blue Days, our team was given clear instructions to conserve the creases and to treat these as evidence of life.”