Over the past few years, the conversation around adaptive fashion has certainly garnered more attention. This year alone we’ve seen a stronger push to center those in the disabled community within the industry, from British Vogue‘s May 2023 covers to Victoria’s Secret’s first-ever adaptive intimates line in partnership with Runway of Dreams, debuted during New York Fashion Week. There’s much more progress to be made, but it certainly is relieving to know that change is happening. Like most discussions about inclusion in fashion, though, the conversation is happening at the professional level, overlooking a crucial peg on the ladder that can lead to institutional change: the classroom.

Some fashion schools and design programs have been ahead of the curve when it comes to adaptive design, fostering in-depth opportunities for students to have a holistic understanding of the category. At Drexel University, for example, the curriculum is set up for students to work on projects based on their interests, needs and trends, which offers an opportunity to address accessible and adaptable design in many different ways, from interdisciplinary projects within fashion design, product design and design-to-merchandising projects with local companies.

Photo: Courtesy of Parsons

“Our students are curious. They’re coming thirsty for a new way of learning and a new way of applying design,” Dr. Ali Howell Abolo, associate professor and program director of Fashion Design, tells Fashionista. “We’re getting these requests, but we’re also able to connect to folks that have these needs or want to work with us. As a competitive, highly recognized fashion design program, folks are coming to us because they realize our abilities, our students’ abilities and the faculty’s abilities to fulfill.”

For Parsons School of Design, the relationship between fashion and disability has been a focus for many years, introduced in larger lectures, partnerships with groups like the Special Olympics and Open Style Lab, core courses where students are paired with a person from the disabled community to co-design a garment and more. The latest iteration of the latter is a course called “Fashion and Disability Justice,” and, according to Dr. Ben Barry, dean of Parsons School of Fashion, it’s all about “centering the wisdom and the knowledge that’s inherent in disability experience and working with collaborators to lead the design process, moving away from a transactional client-designer relationship to one that’s truly about knowledge exchange and sharing, grounded in the learnings and teachings of the disability justice movement and disability community.”

He says the goal of this is, in part, to move away from the idea that disability is a “problem” that designers are expected to “solve,” and towards “actually changing that and seeing disability as inherently a valuable and desirable experience in the world” and making people with disabilities active participants in the process.

Photo: Courtesy of FIT/Smiljana Peros

Dr. Howell Abolo agrees that, to truly understand adaptive design, you have to immerse yourself and interact with the community, which is reflected in the Drexel curriculum.

“We live in such a diverse country and in a diverse world… designers need to be able to reach that population,” she says. “Just as we talk about understanding target markets as a designer, you also need to understand this target market and be able to create products that meet their needs while working within the communities. That’s the piece that’s often missing from any type of design, where we’re designing for a certain population but maybe not interacting with them. That’s what I really like about this model at Drexel: We’re actually working with folks within the community to understand how the design process should work.”

The benefit of learning adaptive design goes beyond strictly meeting the needs of the disabled community. It ultimately benefits everyone, able-bodied and disabled alike. New silhouettes, innovative functions, design advancements — adaptive fashion allows creatives to explore design in a new light, and brings forward new ideas on how we see dress.

Photo: Courtesy of FIT/Erica Lansner

This is certainly the case at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), where fashion design and technical design students have pushed their creative boundaries and innovated within the adaptive design realm for their final capstone projects.

“We definitely teach them to open up their minds and knowledge about what can happen,” says Professor Deborah Beard, FIT’s associate professor and chair of Technical Design and Pattern making.

The results speak for themselves: Beard had one student design a velour, jogging-like suit that was crafted with invisible portals and openings, so the student’s aunt, who was undergoing chemotherapy, could take the treatment while still being warm and comfortable. Another made a baby blanket for blind children that further developed over time, incorporating various learning elements, such as braille, so the user can learn things such as letters and numbers early on.

But advancing adaptive design goes beyond graduation, and certainly extends beyond the lens of fashion designers. That’s where nonprofits like Open Style Lab not only “fill a gap that’s not as prevalent in higher education or schools in general,” but also “find a space where disability groups, communities, local people, designers and engineers could all get together” to create functional and wearable solutions for people of all abilities, explains Grace Jun, assistant professor at the University of Georgia and one of the group’s board member.s

Photo: Courtesy of Open Style Lab

Open Style Lab partners with schools and design programs (such as Parsons), and puts on events for people of all ages, abilities, genders and occupations to create a safe space where everyone is welcome to participate in conversations around adaptive design. Most recently, the organization put on an “Exploring Accessible Footwear Design” workshop in New York City, led by Executive Director Yasmin Keats.

Up to one in four adults in the U.S. have a disability. And yet, adaptive fashion is still considered a “niche” sector. Bluntly put, that specification stems from a long history of ableism and continued efforts to erase the disabled community from the mainstream. Educators and experts are putting in the work to dismantle that.

“There’s a lot of historical evidence that alludes that disabled people have been innovators, designers, hackers — long before we’ve decided to make it more mainstream today or more known in different forms,” Jun says. “It’s not niche, but what are the conditions in practice, in education and of course in fashion as a cultural and social field of study that aligns for greater visibility and more people with disabilities being visible?”

This responsibility doesn’t fall only on educators: Students willing to ask the important questions can also lead to change.

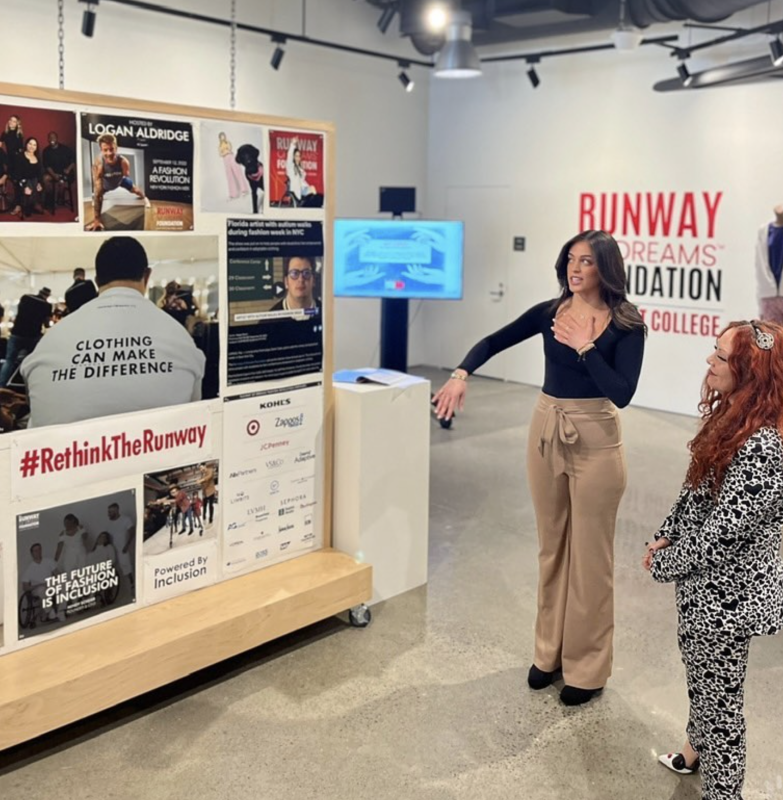

“We could be training people all day long on how to teach these courses and adaptive design, but it’s a multi-pronged effect,” says Mindy Scheier, founder of Runway of Dreams. “We need it from an educator perspective, but we also need it to bubble up from students asking the question, ‘Why aren’t we thinking about how we design this for somebody with a disability?’ Being curious, being vocal about it.”

Photo: Noam Galai/Getty Images

Scheier launched Runway of Dreams in 2014 after her son was diagnosed with Muscular Dystrophy. She’s since used the organization to raise awareness about adaptive fashion and advocate for industry change. It also works with brands on their adaptive product offerings; most recently, it helped Victoria’s Secret launch its first-ever line of adaptive intimates.

“For generations and generations to come, we need to understand that people come in all different shapes, sizes and abilities. Rethinking the way things are designed is critical to making change happen,” explains Scheier. “Upcoming designers and design students need to understand how, if it works for people with disabilities, it will work for everyone. The simple notion of putting magnets behind buttons, because it’s a different way to close a garment, everybody could be using that.”

Similar to Open Style Lab’s interdisciplinary approach, Runway of Dreams encourages people of all disciplines to come together — a mission that’s particularly mirrored in the Runway of Dreams College Clubs.

“You don’t have to be a fashion major to be a part of our college club program, because our college clubs were built to be an extension of the mission of Runway of Dreams,” Scheier says. “This means that our clubs also put on their own adaptive show. And when you put on a show, look at all the different disciplines that you need — you need marketing, advertising, fundraising, model management, design. All of those could have nothing to do with being a design major, but the one commonality is that they’re all learning about this population and what the nuances are to working with people with disabilities.”

Photo: Courtesy of Runway of Dreams

While the call for institutional change has gone from a muffled whisper to a paramount shout, change in how we teach adaptive fashion to the next generation doesn’t just happen overnight. It takes steps to get there.

“I think (the) first (step) is to really invest in their faculty,” Jun says. “I can’t say this enough: I don’t feel like faculty get enough credit for a lot of the hours we put in, especially for the time and dedication it really takes to build up the class and curriculum. The other part I would say is to reach out to nonprofits and groups and organizations like Open Style Lab to partner. This isn’t something you do by yourself… Most of all, it’s really having the person you’re thinking of designing for to be designing with you and to be there presently as much as possible.”

Barry notes how students who enter the workforce with a background in adaptive design are not only more employable, but also have a completely different frame of mind that can lead to industry transformation.

“They’re willing to first have a critical framework to say: If we’re designing around diverse bodies, what’s our perspective? Are we solving problems? Are we inherently valuing all bodies as desirable and fashionable?” he says. “Are we authentically including those communities at every single stage of the design process, from that ideation right to the final prototype? Is the community actively involved in ways where they’re equitably valued, credited and recognized for their labor and brilliance?”

Progress is slow, but it’s being made. And educators remain hopeful for the future to come.

“By designing with disabled bodies that fashion hasn’t centered before (in mind), it actually opens up all of these new aesthetic and fashionable possibilities,” Barry says. “It expands how we design and what we design.”

Want the latest fashion industry news first? Sign up for our daily newsletter.