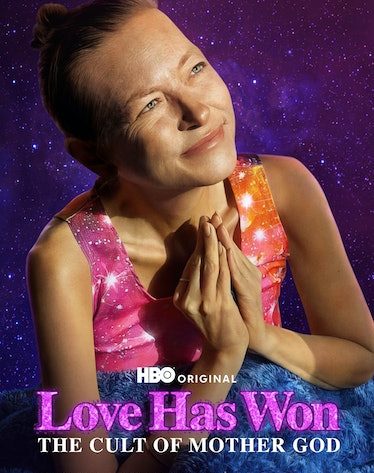

The three-part documentary Love Has Won: The Cult of Mother God (streaming now on Max) is not your typical cult fare. Rather than the usual parade of disillusioned former members looking back at the wreckage, the subjects of the series are very much in the thick of it. Director Hannah Olson connected with the members of a group called Love Has Won just a few weeks after the death of their leader, Amy Carlson, a woman who declared herself to be God. Through interviews with her devotees, snippets pulled from the thousands of hours of Love Has Won YouTube videos and live streams, police body camera footage and more, Olson paints a searing and unsettling portrait of a particular slice of American life. On the heels of the finale’s release, W spoke with Olson about how she managed to make some of the most shocking television you’ll ever see, without being sensational or exploitative.

What drew you to the story of Love Has Won?

What drew me in was that it was a cult story that also felt like a whodunit. What we usually see with cult stories is one charismatic male leader gathering followers, and then the cult implodes because of one of the vices of that male leader—usually sex, money, or power. With this story, I couldn’t tell who was in charge. And the images of Amy Carlson that were published after her death haunted me. I genuinely wondered how that fate could befall someone. How could she possibly go from being a mother of three kids and a McDonald’s manager to being a mummified cult leader?

How did you first hear about the group?

I spoke to a new age scholar at UT Austin. I was interested in how the Internet was contributing to the breakdown of consensus reality, politically, and in how it was happening in smaller microcosms. The questions I was asking about the relationship between class and the Internet and reality led me to this organization. I wasn’t on the search for a cult film, per se. The cult film is such a genre with a specific arc, and this felt different.

The group was a cult by dictionary definition, but as you mentioned, there was a lot of deviation from that norm. There’s usually an element of control and secrecy, but these people were live-streaming everything they were doing, and it seems like they could come and go as they pleased, to some extent. Why do you think people stuck around, and why did Amy’s message resonate so strongly with them?

I think she empowered people to make sense of an often troubled reality. In the United States, we have an idea that you can heal social ills with a feeling or enough willpower. She empowered vulnerable people with a framework for that, and it’s a really attractive framework. I think people stuck around for two reasons. One is that the people in Love Has Won really pooled their finances, and if you’ve given money to something, it’s hard to get out because you don’t have anywhere to go.

The other is that they had created a community. I think a lot about the kind of social communities that form around addiction or people who are gravely ill. If you’ve ever taken care of someone who’s dying, it can feel like you’re in a spaceship. I think that was also at play here. But most of all, once you’ve decided on something in life, whether it’s a relationship or a career or, in this case, a cult, it’s very hard to change.

You were doing interviews with the member of “the team,” as they called themselves, only a couple of weeks after Amy’s death. How did you initially get in touch with them and were they at all reluctant to speak?

I met with the group three weeks after the discovery of Amy’s body. They were very open with me because part of Amy’s mission as they saw it was the disclosure of the truth as they perceived it. They saw the sharing of their videos, photographs, diaries and experiences as an extension of that mission. And initially, while I found some of their beliefs to be very outside of the box—absurd, even—I found the social circumstances that brought them to the group to be eminently relatable. And so I met them from a place of empathy. And I also was careful to be respectful of the way that they were using language, and I called them the names that they asked me to call them. I just met them where they were.

Watching the series, it seems like some of them did eventually leave that world behind and reconnect with their families in the time it took to complete filming. Was it difficult to look back at that earlier footage knowing they had changed since?

The people in Love has Won continue to believe that Amy Carlson was God. And although their social worlds look a little different now, they very much still believe that there was something very powerful about Amy. In some ways, I was waiting for that moment of them going from being inside the belief system to outside of it, and it didn’t come.

You’ve spoken in previous interviews about how the success and appeal of the group are a representation of the failure of the American dream, and particularly of the American healthcare system. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Well, a lot of people in the group believed in big pharma conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories can be very dangerous when they veer into bigoted thoughts or belief systems that then proliferate online. But at the same time, a lot of people within Love has Won had firsthand or familial experience with the opioid epidemic. El Moyra’s father was prescribed Oxycontin and then ended up dying. Andrew, who was one of the Father Gods, was himself trying to recover from an opioid addiction. Especially in the case of opioids, it’s very easy to connect the dots between big pharma and the government and the lack of resources for people suffering from addiction. It’s easier to believe that there is some conspiracy at play rather than the cold facts of capitalism.

And yet there was a capitalist streak to the group. They were surrounded by so much stuff. It was the aesthetic of spirituality filtered through an Amazon lens.

The whole thing felt extremely American to me. Viewers are finding the celebrity worship element to be really funny. But celebrities are the American deities. Consumerism and celebrity worship are definitely a part of the dogma of the group, I think.

There’s also an interesting generational thread in the series. Amy was tapping into this idea of Millennial malaise and disillusionment, but then her children, who are Gen Z, seemed so clear-eyed about the whole thing. It made me feel like Gen Z is better equipped to handle the reality that we’re in than Millennials are.

I was thinking a lot about my generation when I started looking into this story. I was trying to draw the line between the Y2K moment, when we realized all of a sudden that our lives had become tied to computers, and the Trump era and the way that the Internet fragments consensus reality. We choose our own path on the Internet, therefore we choose our own reality. The people in Love Has Won spoke a lot about 9/11 and the 2008 mortgage crisis and the birth of social media. For Millennials, those three events happening in our adolescence and early adulthood shaped and disillusioned a generation. Gen Z seems healthier on social media than Millennials do, because we remember life without it. We have a dopamine hit relationship with it. So it can feel like an addiction really quickly for Millennials. Whereas the Gen Z kids, it’s more like a magazine that was always there. But I think Amy’s kids also have had many years to process Amy’s absence and are good, smart, and well-adjusted kids thanks to the people who raised them.

You used a lot of footage and audio from police body cameras. One of parts that stood out to me was a conversation between an officer and El Moyra, where the officer says something along the lines of, “Not to be insulting, but you seem like an intelligent young man.” And El Moyra responds, “And now I’m here.” That sort of summed up the entire project.

Life can change in an instant. We’re one trauma away from making decisions we never thought we would. That’s the power of an Internet wormhole that can bring you into a completely alternate reality.

One of the more intriguing characters in the series, and perhaps the most mysterious, is Miguel, or Michael. You didn’t have access to him, but his actions seem to suggest that he maintained a degree of distance from the group all along.

My storytelling rule was that unless you’re there, you don’t get to talk about it. I was very careful in this series, because of the sensitive nature of the material, to not speculate about anything and to only include things in the series that I was absolutely sure were true. With Michael, I realized he was the one who had called the police; I watched the body camera footage of him in the Saguache County Sheriff’s Office. As I started poring through the 2,700 YouTube videos, I saw him as one of Amy’s very first followers, and then later learned that the accounts were in his name. So those are the facts—but what Michael believes or doesn’t, I don’t know. He declined to participate in the series.

Do you consider the series to be a cautionary tale?

I think that the human brain is trained to worship, and you need to be careful what you worship. Sometimes the line between the escapism that we so often associate with addiction and the escapism that we can find on the Internet is maybe more direct than we think.