Jiang Cheng is sitting on a brown leather sofa in his airy, high-ceilinged Shanghai studio. It’s 5 p.m., a couple of hours before he usually starts the day. The studio is on the ground floor; up an elegantly swirling staircase are the living quarters, which he shares with his wife, their two daughters, and his father. Once everyone has gone to their rooms to settle in for the evening, Jiang will come back downstairs and begin to paint monumental portraits inspired by art history, Greek mythology, or his imagination, but never from sitters or photographs.

Some of these paintings, which Jiang has collected into a body of work he calls the “U” Series, will be created from start to finish in one three- or four-hour session. Not all are successful, in which case Jiang paints over them—a technique he says he learned from his daughters. One of the paintings in his exhibition at Tara Downs gallery in New York, opening October 20, is of the archangel Gabriel, and it only worked on the tenth attempt, meaning that it is painted over nine other versions. “The paint is very thick,” Jiang tells me through a translator. “So thick it feels different from the other paintings, like Monet when he was painting the Rouen cathedral.”

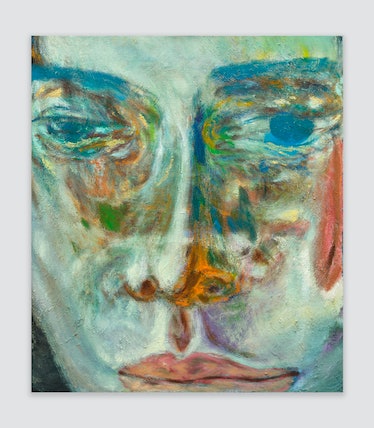

Jiang Cheng, U-133 Gabriel, 2023

Courtesy of the artist and Tara Downs, New York

Jiang was born in 1985 and brought up in Quzhou, a small city near Shanghai, to working-class parents who had nothing to do with the art world, though his mother did calligraphy as a hobby. At school, Jiang realized that he was better at painting than his classmates, and it dawned on him that art might be open to him as a profession. He gleaned inspiration from cartoons and, later on, from books on Western old masters like Leonardo da Vinci. “I didn’t have the opportunity to go and see art exhibitions,” he says. He studied art at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, and then in 2012 went to Berlin for his MFA, returning to China once it was completed. He worked in Beijing but left for Shanghai in 2020 when the district he had been working in was torn down by developers. He feels that Shanghai’s art scene is more international and outward-facing than Beijing’s.

Jiang shows me a huge painting, taller than a person, on which the oil paint is still drying. It depicts the archangel Michael, who old masters like Raphael painted wielding a spear and battling a dragon. Jiang takes a very different tack, with a tight focus on the angel’s countenance. “I found that there has never been a close-up of Michael’s face, and I really wanted to show the emotion beneath,” Jiang says. The result is a dynamic, psychologically acute portrait in which one set of features seems to hover on top of another, somehow evoking a complex struggle between conflicting states of mind.

The picture is made stranger because other distinguishing features, like race and gender, are blurred. “The ambiguous racial identity is because when as a Chinese person I see Western images, they become a part of my perspective,” Jiang explains. “And as for sexual identity, my work always challenges abstractions or concepts like gender. In the realm of art, gender assumes a mercurial or enigmatic quality. In my paintings, the ambiguous can become the authentic.” His fascination with angels isn’t just art historical, but religious. “I’m a Christian myself,” he says.

The way the paintings are created is, by his account, also somewhat mystical. Jiang describes it as “the shiver,” a process in which the movements of the body take over the thoughts of the mind. To get in the zone, he plays different kinds of music at random—the music gives him energy, and the randomness provides contrasting emotions and rhythms. Then he lets his martial arts-trained body do what it will over the huge canvases. “Because of the size of the canvas and my closeness to it, I can’t see the whole image,” Jiang explains. “For instance, sometimes I will paint an eye, but I can’t really see it and when my body moves I will paint another eye over the top.” Once the painting is completed, he gives it a title. “I won’t be thinking ‘I’m painting Michael in this image’,” Jiang says. “I paint the close-up faces first and name them after. The naming process is kind of a re-imagining of the painting.”

Jiang also has another range of paintings, called the “E” Series, which are more conventional portraits at a less monumental scale. Though they’re not created while using “the shiver”—he is fully conscious of the images he is making—they also often depict mythological heroes as enigmatic, indeterminate youths. He shows me a portrait called Achilles, where the Greek warrior has curly hair, sensuous lips, downcast eyes, and seems to be wearing a mauve blouse. “I was thinking of the story where he was dressed as a woman before going on the battlefield,” he says.

Jiang’s working day may be short—it starts at 7 p.m. and finishes around 11:30 p.m.—but it is taxing. The day is taken up with reading and research for ideas for paintings. After making a work, he’s so tired that he must take a few days off. He’s also planning a vacation with his family. “Maybe Paris,” he says. It’s a city teeming with potential inspiration for his pictures of saints, angels, and mythological figures who seem, through his eyes, not just remarkably modern, but vividly real.