When Marc Jacobs calls at the end of June, it’s been four days since his fall 2023 show at the New York Public Library, on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. People were still trying to figure it out. As has been the case for the past few years, the presentation was off-calendar, bare-bones, and far more intimate than the grand theatrical spectacles Jacobs once produced. A lot has changed for the designer since he did away with his jaw-dropping sets and scaled back his collections, which are now sold in a single store, Bergdorf Goodman. But audiences still look to Jacobs for direction, and he delivers—provocatively, as usual.

This time, he presented the collection only as a finale: The models marched up and down the runway in a line as they would have at the end of a show, without first coming out individually, which barely gave the audience a chance to see the clothes. The whole thing took approximately three minutes. What’s more, his normally informative program notes were this time composed by ChatGPT, the artificial intelligence bot that churns out banal, computer-generated copy on demand, as if Jacobs were making a statement about the steady devaluation of the creative class in the wake of advancements in technology. Or maybe it was about the relentless speed of today’s fashion industry, or just the general climate of instant gratification and nonexistent attention spans: The Marc Jacobs fashion show, the text read, was “a striking fusion of masculine tailoring and feminine elegance.” Naturally, people wanted to know what Jacobs was up to, but the designer had sped off in his Lamborghini Huracán before anyone had the chance to ask.

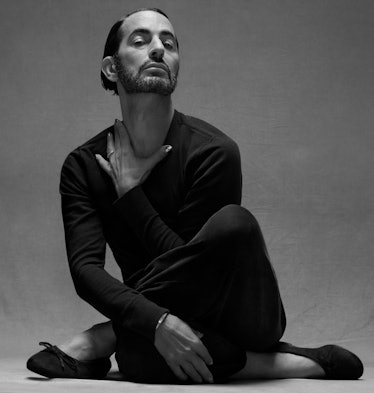

Marc Jacobs wears his own clothing and accessories. Photographed by Ethan James Green. Makeup by Sam Visser for Dior Beauty at art partner; Lighting Director: James Sakalian; Photo assistants: Sam Kang, Kaitlin Tucker; Makeup assistant: Shimu Takanori; Production assistant: Andy Martinez.

Marc Jacobs

From left: Hunter Pifer, Thursday, Cecilia Wu, Reece Tong, Zahra Traore, Valentine, Madelyn Whitley, and Alay Deng in Marc Jacobs clothing and accessories.

Photographed by Ethan James Green; Styled by Charlotte Collet.

Having worked in the industry for some 40 years, having seen conversations shift from the dominance of brick-and-mortar stores to the perils of online retailing and AI, Jacobs speaks, when we connect, without a hint of disdain for the modern world. Whatever critics might have thought about his show, he wanted to be clear he was not making light of anything. He remembers that this past summer, when he couldn’t find the right words to describe his work, it was his assistant Nick Newbold who suggested they try ChatGPT. Jacobs loved the idea—even though it felt a little dangerous. “I think in a positive way, it was the universe, and all of this history I’ve had, and all of the ways we used to do things, coming together and saying, ‘Well, this is exactly where you’re supposed to be in this creative process. You have made a decision to have this be the program notes,’ ” says Jacobs. “So even though it didn’t feel like a creative decision at the time, it was a creative decision.”

Jacobs turned 60 this year. His brilliance has always been his ability to tune into a moment and define it before anyone else, and to find inspiration in life’s imperfections. For him and other designers who managed to create something marvelous and tangible in their lifetimes—that is, a real brand with staying power, with their name on the door—it becomes a necessity to constantly question themselves. These are not just the survivors of a career amid fashion’s endless thrusts and parries. They are the conquerors.

Looking at those who have remained at the helm of their own labels for decades, it’s hard to describe how phenomenally impossible that goal must have looked when they were starting out. Jacobs was famously fired from his first job, at Perry Ellis, following his grunge collection in 1992, but his groundbreaking work for Louis Vuitton established a new archetype: the multitasking, globe-trotting, insanely rich designer. Look at Michael Kors, who had to file for bankruptcy protection in 1993 after a decade in business but went on to become an international powerhouse after working for Céline in Paris and ICB in Tokyo. His own company went public in 2011, and Kors, 64, is now a billionaire. These are feats to be celebrated for the sheer audacity it took for the designers to believe in their own talent—and to be proven correct.

Donatella Versace wears Versace clothing and accessories.

Photographed by Andrew Archeos. Courtesy of Versace.

Versace

Emily Ratajkowski wears a Versace gown, earrings, and shoes.

“I think my staying power can be attributed to my determination and strong will,” says Giorgio Armani, who, at 89, is easily the most successful independent designer in the history of Italian fashion, with a net worth of $12.7 billion, according to Forbes. “I learned very early on that while other people’s opinions do matter, what truly counts is staying true to my vision.”

Others, like Miuccia Prada, 74, and Donatella Versace, 68, have molded family businesses into establishment brands with enormous clout and revenues, and easily definable legacies that will continue to resonate long after they are gone. After 42 years in business, Kors can’t say he’s surprised to have succeeded doing a job that he loves. He still thinks of himself as that kid from Long Island who started selling fashion sketches when he was just 16. He once told the actor Melanie Griffith that he identifies with her character Tess McGill, in Working Girl—he’s just a working guy from the outer boroughs with an endless drive to succeed in the Big City. “What surprises me after all these years is that there are some people who don’t even realize that there is a person named Michael Kors who still goes to work every day, who still designs the product,” he tells me. “I’ve had TSA people see my name and ask, ‘How long have you worked at Michael Kors?’ ”

When Kors, who is known for his jet-set vision of American sportswear, won the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America in 2010, at the ripe old age of 50, he became one of the youngest designers ever to receive such an accolade. Jacobs was given the same award the following year, at 48, and it occurred to Kors that something fundamental had changed in the fashion world that he had known since his youth: His generation had become the establishment, and there weren’t many designers still around who could say they had made it that far. “In my mind, we had been called ‘Young Designers’ for so long that it was kind of like we were young designers forever,” says Kors. “When Marc got his award, I looked at him and I said, ‘I guess we’re the Old Young Designers now.’ ”

Giorgio Armani wears his own clothing.

Photographed by Tristan Fewings. Getty Images.

Armani

from left: Danielle Zinaich, Liisa Winkler, and Mini Anden in Giorgio Armani clothing and accessories.

Why did they last when others did not? Many iconic designers have had full, celebrated careers and chosen strategic and hugely profitable exits, selling their labels to big corporations and moving on to their next lives—think of Donna Karan and her zen wanderings, Calvin Klein spending years designing his minimalist mansions, and now Tom Ford, who struck a deal with Estée Lauder for $2.8 billion last November and plans to go back to directing movies in Hollywood. But for the majority, fashion is a tough game, littered with examples of designers who saw their promising careers crash and burn, and others who headed for the door rather than bend their vision to the will of a new owner. There’s no escaping the sense that it’s also becoming harder for newcomers to hold on to lucrative jobs at luxury houses as the merry-go-round seems to spin ever faster.

Part of this has to do with the continually expanding job description of a designer, whose duties have always required an intense balancing act between the process of creation and the management of everything else that happens in a business—as well as a willingness to adapt to the times. “I’m not just a fashion designer,” says Kors. “I’m in media. I never knew that the word ‘content’ would be something a designer would have to think about.” Now every collection is crafted with a narrative that unfolds over the course of a season, with elements directed to audiences wherever they are consuming fashion—be it in a store, online, or on social platforms. “Remember,” says Donatella Versace, the undisputed queen of creating viral moments, “that Google invented Google Images because of Jennifer Lopez wearing the Versace jungle-print dress. I have seen myself designed as an avatar, and I have seen some experimental work in AI. I like to surprise people—I am inspired by technology and creativity working together.”

Tory Burch, who founded her label in 2004, was one of the first to emphasize a primarily direct-to-consumer model, with both e-commerce and online content channels. What sounds normal today was considered wildly disruptive at the time. “People told me that I was crazy, and they thought it was really strange that I included other designers’ work on our website with ‘Tory Daily,’ which was one of the first fashion blogs,” says Burch.

Michael Kors wears his own clothing and accessories.

Photographed by Andreas Laszlo Konrath. Grooming by Candice Forness for Candice Forness Botanicals.

Michael Kors

Candice Swanepoel wears a Michael Kors Collection jumpsuit, belt, and shoes.

Today, Burch has 4,500 employees; in the head office, 80 percent of them are women. Unlike most designers who create a philanthropic foundation once they are established, Burch flipped the script and started a fashion line to support her philanthropy: Her foundation has awarded more than $100 million in low-interest loans to female entrepreneurs in the United States. “That was my business plan, literally thinking about positive change, and I didn’t have experience in any of the above,” Burch recalls. “I’m slightly embarrassed hearing myself say those words after 18 years, now knowing what that means and the amount of excruciatingly hard work that unfolded.”

Two things stand out when you look at the histories of those who have stood the test of time.

First, and most important, each designer has a distinct point of view and a unique story to tell through their clothes, their lifestyle, and even their personal appearance. Jacobs is the creative ringmaster of American fashion. Tory Burch sells accessible luxury and prioritizes having community impact. Rick Owens practically owns the concept of gothic avant-garde. Stella McCartney’s ethos revolves around cruelty-free clothing and innovative materials such as vegetarian leather. Giorgio Armani is known as the first to capitalize on the power of the red carpet—has any Oscar winner not worn one of his creations at some point? Donatella Versace is famous for being Donatella Versace—once an over-the-top diva who epitomized the label’s fierce body-con glamazon aesthetic, now a distinguished role model for the modern female CEO.

From the time she was a young woman, Miuccia Prada’s fashion philosophy was built almost entirely on her own resistance to anyone telling her what she should do or how she should dress. She wore Saint Laurent to women’s liberation protests and has been a contrarian ever since. “I always thought you should be able to go to a party and also take your children to school and never be ashamed of what you are wearing,” says Prada. “I don’t want to have to dress differently for different social plans. I would have felt uncomfortable if I would have had to change my way of dressing for whatever I have to do.”

Miuccia Prada wears Prada clothing; her own jewelry.

Photographed by Brigitte Lacombe. Courtesy of Prada.

Prada

from left: Meghan Collison, Amanda Murphy, and Lineisy Montero in Prada clothing and accessories.

Kors, despite his self-deprecating sense of humor, really does project the glamorous image of a jet-setter in his aviator sunglasses and perfect suntan. He became a household name when he appeared as a judge on Project Runway for 10 seasons, beginning in 2004, and was indelible in viewers’ minds for his crafty quips. “Of course, that was a long time ago, so there’s a whole new generation who didn’t watch Project Runway, and they only know the product,” says Kors. “But does it help to have confidence? To have a personality? Well, it doesn’t hurt to be stylish.”

The second thing these designers have in common is that they have all triumphed over adversity, whether it be substance abuse or financial calamities or the loss of a cherished partner, and done so while constantly in the public eye. Versace remembers the learning curve she faced when everyone questioned her ability to steer the label after the 1997 assassination of her brother Gianni. “It probably was harder on me because I am a Versace, and the magnifying glass was strong,” she says. “Now that I have been leading the company for longer than my brother, and brought in new business partners so successfully, hopefully the questions have been more than answered.” She wasn’t confident in herself then, but she is now.

Still, there is no blueprint for how to get ahead in fashion without really, really trying. For most designers, success had to do with drive, talent, and being in the right place at the right time. And the 1990s were one of the best times to be starting out in fashion; the decade saw a fabulous explosion of fin de siècle creativity bankrolled by tycoons who were in a race to build what would become today’s massive luxury conglomerates. Both Jacobs and Kors benefited from their long associations with LVMH, while Stella McCartney was snapped up by what was then known as Gucci Group.

Rick Owens wears his own clothing.

Photographed by Karim Sadli. Production by Brachfeld; Lighting Director: Antoni Ciufo; Digital Operator: Aurentin Girard at Imagin Paris; Photo Assistants: Chiara Vittorini, Vassili Bocle; PostProduction by Imagin Paris.

Rick Owens

From left: Finlay Mangan, MJ Herrera, Mika Nobles, Hong Lin, Delilah Koch, and Duot Ajang in Rick Owens clothing and accessories.

“We were part of this really young, naive, kind of rebellious moment when people felt they had permission to start their own brands,” says McCartney, who was fresh out of Central Saint Martins and had started a fledgling business based on her graduation collection of vintage lace dresses when she was suddenly hired as Chloé’s youngest-ever creative director, in 1997. “It was such a rare period in fashion. I don’t know if that stuff happens anymore so naturally and organically and effortlessly.”

By 2001, she was being courted by Tom Ford and his business counterpart, Domenico De Sole, to take over Gucci. “Tom said they would stop doing fur, and I said, ‘That’s great, but are you aware that I don’t do leather, either?’ And his face dropped, and the blood was drained,” says McCartney, who is now 51. “That was an impossible ask on my side at the time, and I was so heartbroken because I really wanted to go there. A week later, he called me up and said, ‘Look, I’ve talked to Domenico. Do you want to start your own label with us?’ I was like, ‘Hell, yeah!’ ” (Gucci Group was later renamed Kering; in 2018, McCartney took back control of her label and then aligned with LVMH.)

Rick Owens began selling his dark, unconventional, and decisively independent designs out of Los Angeles in 1994 through the groundbreaking retailer Charles Gallay. He found himself facing a quandary when Vogue sponsored his first runway show in 2001, suddenly making him the toast of fashion. “I really wasn’t confident that my very slow, quiet little aesthetic would be able to sustain the glare of the runway spotlight for very long,” says Owens, who is now 60. “I mean, I could do one or two shows, but after that I wasn’t going to change enough to satisfy people who needed more excitement for the whole fashion scenario. I suspected that I was going to become the Fashion Week weirdo after a while.”

Tory Burch wears a Tory Burch top, pants, and shoes; her own jewelry.

Photographed by Pamela Hanson. Hair by Robert Harrington; makeup by Berta Camal; photo assistants: Milton Arellano, Emmanuel Rosario. Special Thanks: Daylight studios, NYC.

Tory Burch

From left: Alex Consani and Colin Jones in Tory Burch clothing and accessories.

The following year, he was asked to become the artistic director of Revillon, a fur house so old that it’s mentioned by Proust; it was an experience that gave him validation in Paris and the confidence to build his life there. Over time, he has come to enjoy every part of the creative process—even the shows, which now include pyrotechnics and fog machines. “You have to prove your relevance four times a year,” he says, referencing his men’s and women’s collections. “But it’s kind of like a birthday party. You’ve fulfilled a cycle and a circle, so it’s a pagan ceremony with lots of people that I like.”

That’s what’s great about designers sticking around for so long—all the things that used to frustrate them have become things they love. At the time we speak, Burch, 57, is in Paris and leaving the next day for her much-delayed safari honeymoon in Africa. It’s been so long since she took a vacation that she can’t remember when it last occurred to her to even want one. She married Pierre-Yves Roussel, the former LVMH chairman and CEO who is now CEO of her business, in 2018. Since Roussel joined the company, she’s been delighted to focus on design. And, like any great designer, she has her eye on the future. “I’ve always been like, ‘How do we build a company that has staying power and that is here beyond me?’ ” says Burch. “That’s something I’m very interested in.”

One idea would be to look at Armani’s example. He has fiercely maintained control of his empire while juggling the dual roles of designer and chief executive for much of his career. It was the death, in 1985, of his founding partner, Sergio Galeotti, the young architect who swept Armani off his feet and persuaded him to strike out on his own, that forced Armani to become an entrepreneur. He considers himself lucky now, having so many dedicated family members still working for the company, including Roberta and Silvana Armani, the daughters of his late brother, Sergio, and Andrea Camerana, the son of his sister, Rosanna. “I have always worked this way, staunchly defending my independence, because I am convinced that is the only way to create something relevant,” says Armani. “The paradox of independence has certainly created a rather unique reality in today’s fashion landscape. I am a black swan in a world of very powerful conglomerates.”

Stella McCartney wears Stella McCartney clothing and accessories. Stella McCartney bags.

Photographed by Venetia Scott. Hair by Eamonn Hughes for Sam McKnight products at Premier Hair and Makeup; Makeup by Chynara Kojoeva for Stella McCartney Beauty; Photo Assistants: Clementine Saglio, Michael Hani.

Stella McCartney

From left: Amara, Hanne Gaby Odiele, Remington Williams, and Briana Michelle in Stella McCartney clothing and accessories.

Even after so many years, for all these designers, the road ahead will be full of unexpected twists and turns—but they want to enjoy the ride for as long as they can. What matters to them is to keep moving forward. “I don’t believe that I’ve ever made a perfect collection—I always find fault and I always think we could do better,” says Jacobs. “That’s why it’s great that we constantly get the chance to do another one. Success, to me, isn’t a final thing. I’m not successful because I’ve done something—I’m successful because I keep getting to do that thing.”

Models: Hunter Pifer at Q Management; Thursday at The Society Management; Cecilia Wu at Women Management. Reece Tong at Marilyn-NY; Zahra Traore at Elite; Valentine at Heroes Models; Madelyn Whitley at New York Models; Alay Deng at State MGMT. Emily Ratajkowski at dna Model Management. Danielle Zinaich at The Lions Management; Liisa Winkler at New York Models; Mini Anden at The Model Coop. Candice Swanepoel at The Lions Management. Meghan Collison at New York Models; Amanda Murphy at IMG; Lineisy Montero at Next Models. Finlay Mangan at IMG; MJ Herrera at One Management; Mika Nobles at Skorpion; Hong Lin at Kollektiv MGMT; Delilah Koch at Heroes Models; Duot Ajang at Muse NYC. Alex Consani at IMG; Colin Jones at Women Management. Amara at Next Models; Hanne Gaby Odiele at Women Management; Remington Williams at Heroes Models; Briana Michelle at The Industry.

All fashion images photographed by Ethan James Green and styled by Charlotte Collet. Hair by Jimmy Paul for Olaplex at Susan Price NYC; makeup by Sam Visser for Dior Beauty; manicures by Megumi Yamamoto for Chanel Le Vernis at Susan Price NYC. Casting by Piergiorgio Del Moro and Samuel Ellis Scheinman at DM Casting. Set design by Dylan Bailey.

All fashion images Produced by AP Studio, Inc.; Executive Producer: Alexis Piqueras; Producer: William Galusha; Production Manager: Hayley Stephon; Production Coordinator: Babe Lawrence; Lighting Technician: James Sakalian; Photo Assistants: Sam Dong, Ethan Greenfield, Anthony Conklin; Digital Technician: Nickolas Rapaz; Retouching: Dtouch; Fashion Assistants: Sofia Amaral, Paget Millard, Tyler VanVranken; Production Assistants: Linette Estrella, Dom Nadal, Ariana Kristedja, Cameron Bevans, Dakota Caulfield; Hair Assistants: Tomoko Kuwamura, Felicia Burrows, Christina Rendall; Makeup Assistants: Shimu Takanori, Chichi Saito, Juan Jaar, Iona Moura; Manicure Assistants: Mayumi Abuku, Akane Mikhaylov; Set Design Assistant: Julian Passajou; Tailor: Justin Bontha at 7th Bone Tailoring.