If there was one thing that prevailed in 2023, it was the slew of record-breaking tours by some of the world’s most influential musicians, who descended on venues in each corner of the earth to play for the hundreds of thousands of fans that keep them firmly thrust into the limelight. Despite the bright lights of some of the biggest international stadiums, however, the calibre of such events habitually come with a darker side.

Fast fashion has regularly found itself at the forefront of discussions between sustainability and the industry as a whole, with the category typically deemed by experts to be one of the most polluting. Meanwhile, despite the heightened awareness surrounding the pollution music tours generate in terms of global transportation, the sector has managed to scrape by without being inherently linked to the tribulations of damaging fashion habits, in spite of the plainly clear intersection between the two.

Rising concern for this has recently been highlighted by Remake, a global advocacy group focused on the sustainable and ethical development of the fashion industry. Speaking to FashionUnited, Remake’s chief marketing officer, Katrina Caspelich, said of the matter: “In the age of the influencer, concerts and fashion festivals are the epicentres of content creation with the goal of turning out never-before-seen looks. However, it’s not without its environmental drawbacks.”

Artists’ identities become central to concert culture

Between the wardrobes of the artists and those of the fans, there are an array of angles in which fast fashion giants can manoeuvre themselves into the space. This rings particularly true for “concert culture” as a whole, which has contributed to an increased emphasis on themed attire that ties in with the identity of the artist at hand. While fans attending Harry Styles’ ‘Love on Tour’ came adorned in an abundance of feathers and velvet, at Beyonce’s ‘Renaissance’ the ‘Beyhive’ – the name fans have coined for themselves – donned head-to-toe glitter and Taylor Swift’s ‘Swifties’ sported all of the above, combined.

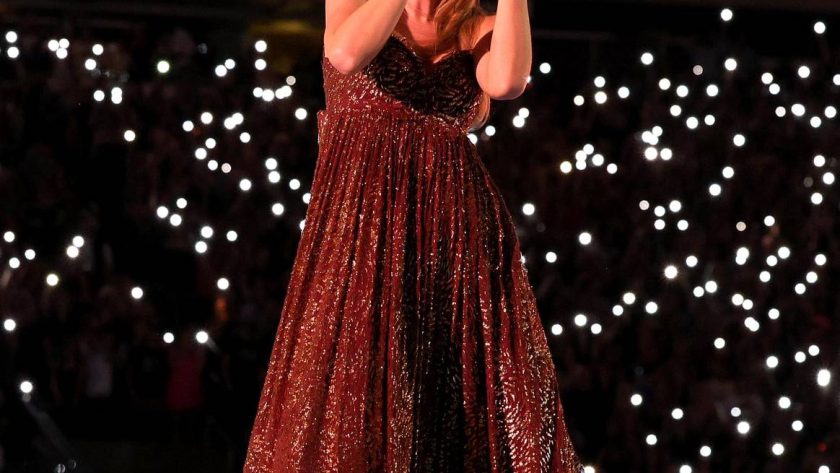

Revolving wardrobes are also evident on stage. Each evening of Renaissance, Beyoncé has graced her audience with never-seen-before high-end garments and gowns – namely by the likes of Loewe and Balmain, signalling their relevance to pop culture and spotlighting the brands to potential new buyers. Meanwhile, for her own Eras Tour, Swift rotates between approximately 13 different outfits in one night – many of which also change per city. Each one-of-a-kind piece contributes to the theatrics of the show, yet also has viewers yearning for replicas – which fast fashion brands are more than happy to supply.

Speaking on this element, culture strategist for Fashion Snoops, Nico Gavino, said on the evolving ties between an artist and their fans: “Music has a long relationship with dress, dating far back into antiquity. However, the focus has more recently shifted beyond the dress of the main performer, but also the dress of the audience as participants in the concert. The rise of digital media has given audiences a new kind of relationship with musicians that is tied closely to their identity, so the concert becomes a place of highly emotional self-expression and interconnectivity. This is ultimately reflected in the increasingly elaborate looks people wear to concerts.”

It was this issue that has been an area of concern for Remake recently, explored in order to highlight this often unspoken factor in the world of touring, concerts and festivals. On this matter, Caspelich said: “Influencer culture is real. Public figures have the power to affect purchasing decisions and the values of their fans and followers. It’s a power they should take seriously. As public figures, musical artists are imperative to driving and dictating the trends we see; they allow their followers to envision what lifestyle could be attained if only they just wore it too. Concert, or festival, culture has definitely influenced consumer behaviour and consumption patterns. In fact, critics say that these days, going to a concert or music festival like Coachella, has become less about the music and more about the ‘see and be seen’ Instagram fashion culture that attendees exploit through their outfit choices.”

Influence extends beyond the stage

In Caspelich’s eyes, the influence over consumption comes less from the artist’s wardrobe, however, and more from the artist or influencer themselves. As such, the momentous influence these individuals hold can also be seen outside of music events. For example, Swift’s brief appearance at a National Football League (NFL) game amid dating rumours with Chief’s tight end Travis Kelce influenced a 400 percent spike in the player’s own jersey sales within 24 hours. Critics were concerned over this figure as any possibility of the duo going separate ways could result in a hoard of discarded American football shirts in response.

A similar mindset was shared by Fashion Snoops’ Gavino, who said: “Today, the relationship between concert culture and fast fashion is not so much rooted in what the performer is wearing on stage, rather the relationship stems from audience members taking inspiration from the artist’s latest work and specific references to the artist’s career. While these collective cultural phenomena do end up influencing fast fashion, it doesn’t necessarily mean that concert-goers are a major culprit of the fast-fashion problem.”

So, what can public figures do to sidestep or even erase the culture of consumption that has been built around their status? For Remake’s Caspelich, public events are a perfect occasion to take a stand for sustainability and ethical clothing choices. She added: “Celebrities have such great influence in the mainstream media today, so promoting a change in behaviour, like re-wearing an outfit multiple times, encouraging fans to be creative in their concert outfit choice by challenging them to rock or upcycle pieces they already own, or opting to not create/sell any new concert merchandise can go a long way and even set new trends that can better the environment and the lives of the women who make our clothes.”

As Caspelich mentioned, it also isn’t just musicians and their tours that contribute to such behaviours. Festivals have become a breeding ground for statement-making fashion, and therefore a hub for brands that are eager to sway the perceptions of consumers. Many retailers plan for months ahead of the anticipated spike in sales that festival season typically brings, with many festival-goers often seeking out entirely new wardrobes, only to potentially throw items away after one use. Therefore, critique must of course also fall on the brands that cater to and promote this overconsumption in a bid to profit off such behaviour.

Throw-away festival collections heighten concerns

It is this aspect that Caspelich is particularly critical of, noting: “Festival season has turned into more of a fashion show than a music festival. Brands then capitalise on this and come out with ‘festival lines’ where they produce an absorbent amount of fast fashion that will rarely be worn more than once or fall apart. Even if it’s donated, the likelihood of these pieces ending up in a landfill is high. And today, since most fast fashion pieces are blended with polyester, spandex, nylon and acrylic, it’ll take close to 200 years for them to decompose fully. In the meantime, decomposing clothes contain dangerous chemicals, microplastic fibres and release greenhouse gases, putting both the planet and the health and well-being of communities near landfills, especially in the global south, at risk.”

When asked what brands and retailers could do to help, Caspelich’s solution was straight-to-the-point: brands must stop producing so much product, especially when the corresponding product contributes to this environmentally unfriendly mode of consumption. Similarly, Remake itself has also set about encouraging consumers to disengage from these processes, a mission that it pushes through its #NoNewClothes challenge.

If accepted, participants must agree to buy no new clothes for 90 days, and therefore either opt to purchase nothing at all or prioritise reuse and resale options. The goal of the initiative is for consumers to be able to assess what is already in their wardrobes in order to “reduce their carbon footprint, build healthy psychological habits, limit the waste they send to landfill, and keep their hard-earned (money) from companies that don’t share in their values”, Caspelich elaborated.

For Gavino, the solution to counteracting waste as a result of concert culture lies in rental solutions, bringing a concept already favoured by wedding guests, for example, further into the world of eventwear. Similarly, the trend expert also highlighted the importance of sustainable materials – such as responsibly-sourced or biodegradable – which he said should be integrated by brands that cater to concertgoers. In conclusion, Gavino added: “Finally, I would also encourage consumers to build a secondhand look or even borrow from friends and family for special events. Overall, brands should consider their impact holistically, from seed to shelf.”